In digital forensics and incident response, reliable storage isn’t a luxury — it’s a requirement. Whether you’re capturing evidence from a live system, processing large data sets with specialized tools, or running a virtual machine in the middle of a case, storage throughput can make or break your workflow.

The challenge? Reported specifications from manufacturers often don’t tell the full story. A drive rated for up to 400 MB/s might only deliver a fraction of that in real-world use. And performance isn’t determined by the drive alone: the quality of your USB cable, the number of hops between your system and the media (direct vs. through a hub), and the system’s own caching behaviors all play a part.

To eliminate the guesswork, I built Crabwise, a simple USB benchmarking utility designed with forensic workflows in mind.

How Crabwise Works

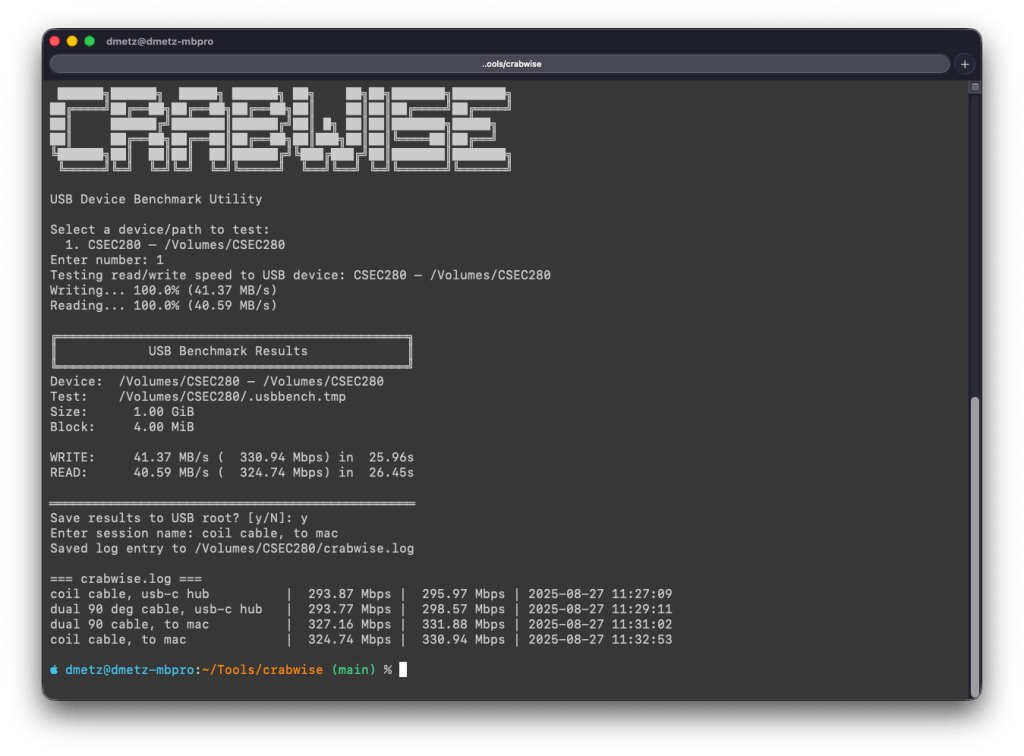

Crabwise calculates read and write speeds by creating a temporary file on the target device and measuring throughput under direct (uncached) conditions.

- Write Test: The tool writes a pseudo-random 1 GiB file (size adjustable) to the USB drive in blocks, ensuring that system caching doesn’t skew results.

- Read Test: It then reads the file back from the device, again bypassing caches, so the reported numbers reflect device-level throughput rather than RAM speeds.

- Progress Feedback: While testing, Crabwise shows real-time percentages and MB/s estimates, so you can spot performance bottlenecks as they happen.

The result is a clean, standardized benchmark of the USB device’s true performance.

Building a Reference Table

One of the most useful features in Crabwise comes after the test: you’re prompted to save the results to the root of the device. If you choose to do so, Crabwise appends the results to a simple log file called crabwise.log.

Each entry includes:

- Session name (you provide this — e.g., “coil cable via hub” or “direct to Mac”),

- Read speed,

- Write speed,

- Timestamp of the test.

When you cat the file, you get an instant side-by-side comparison of your runs:

=== crabwise.log ===

coil cable, usb-c hub | 293.87 Mbps | 295.97 Mbps | 2025-08-27 11:27:09

dual 90 deg cable, usb-c hub | 293.77 Mbps | 298.57 Mbps | 2025-08-27 11:29:11

dual 90 cable, to mac | 327.16 Mbps | 331.88 Mbps | 2025-08-27 11:31:02

coil cable, to mac | 324.74 Mbps | 330.94 Mbps | 2025-08-27 11:32:53Over time, this builds into a practical reference table that lets you quickly compare how different cables, hubs, and ports affect performance. What looks like a subtle cabling change can sometimes mean the difference between a VM booting smoothly or crawling.

Closing Thoughts

In forensic and investigative work, you don’t always get to choose the hardware you’re handed — but you can make informed decisions about how you connect and use it. Tools like Crabwise give you a way to validate your environment, document your results, and avoid unpleasant surprises when timing matters most.

Whether you’re testing cables, validating a new hub, or verifying a forensic workstation setup, Crabwise turns USB benchmarking into a repeatable, documented process.

Download crabwise from GitHub: https://github.com/dwmetz/crabwise/