Malware authors often use file masquerading—disguising malicious executables as seemingly harmless files—to bypass both user scrutiny and automated defenses. A classic example is an executable file with an image extension, such as `.png`, that actually contains a Windows PE binary. To help address this challenge, the Mismatch Miner utility, written in Rust and part of the MalChela malware analysis toolkit, introduces a practical approach for uncovering these deceptive files using YARA rules.

Why File Masquerading Matters

File extension spoofing remains a simple yet effective evasion tactic. Users and some security tools may trust files based on their extensions, ignoring the underlying content. Attackers exploit this by renaming executables with extensions like `.jpg` or `.png`, hoping to slip past defenses. While this technique is not new, it continues to be relevant due to its effectiveness and the limitations of extension-based filtering.

That said, this method should be seen as one component of a broader detection strategy. While it is effective for catching executables disguised as images or documents, it does not address more sophisticated evasion tactics, such as fileless malware or executables embedded within other file formats. Additionally, some legitimate software may use unconventional file extensions, so results should be reviewed with context in mind.

Mismatch Miner: Approach and Implementation

Mismatch Miner is designed to scan a directory for files with extensions that are commonly abused for masquerading, including popular image formats. For each candidate file, it leverages YARA—a widely used pattern-matching tool in malware analysis—to check for the presence of the “MZ” header, which marks the start of Windows executable files. If a file’s extension suggests it is an image, but its header indicates it is an executable, the tool flags the file and reports its name, full path, and SHA256 hash, to support further investigation.

Mismatch Miner offers a practical solution for identifying a common malware evasion technique: executables disguised as benign files. By combining Rust’s performance with YARA’s pattern-matching, it provides security analysts with a reliable tool for uncovering hidden threats. While not a panacea, header-based mismatch detection is a useful addition to any malware analysis workflow, helping to close a gap that attackers continue to exploit.

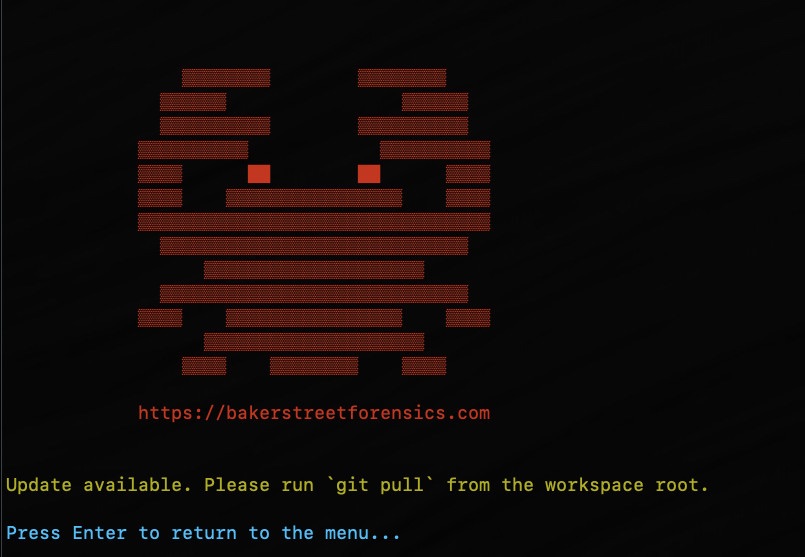

Mismatch Miner is bundled with MalChela, the YARA & Malware Analysis toolkit. If you’ve already installed it, a ‘git pull’ from your workspace directory should get you the new feature.