String analysis is a cornerstone of malware investigation, revealing embedded commands, URLs, and other artifacts that can expose a threat’s intent. mStrings, a Rust-based tool, simplifies this process by scanning files, extracting meaningful strings, and structuring results for efficient analysis.

At its core, mStrings is more than a simple string extraction tool. It integrates regex-based detection rules to identify key indicators, offering a refined approach to analyzing malware artifacts. In addition to console output it also presents data in a structured JSON format, allowing for seamless integration into other security workflows.

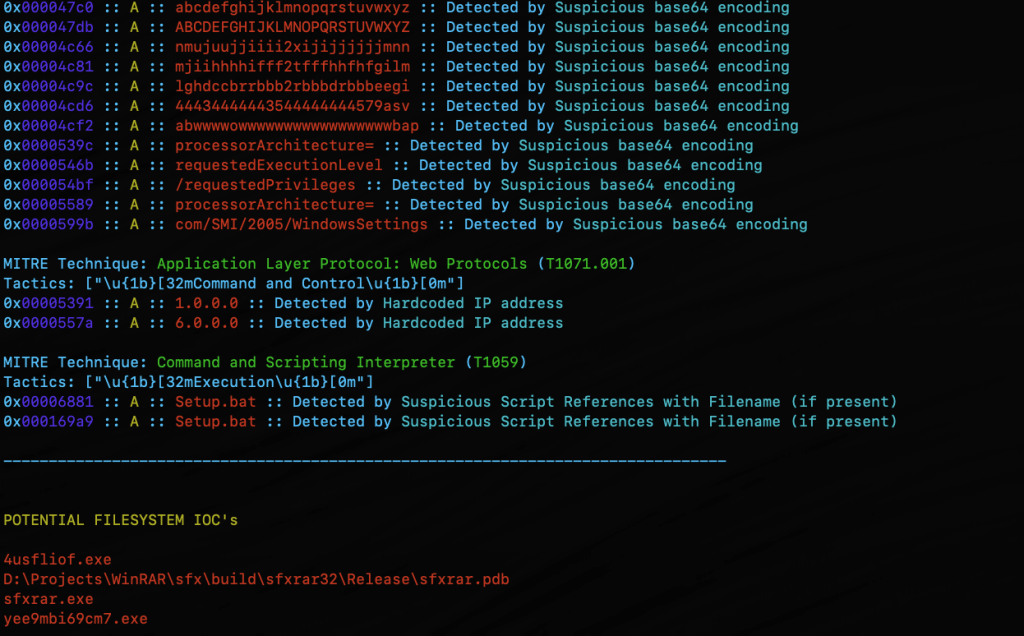

In addition to specialized string searching, mStrings detections associate results with MITRE ATT&CK. When malware indicators map to known MITRE ATT&CK techniques, analysts can quickly understand the intent and behavior of a threat. Instead of just seeing a suspicious string, they can recognize that it corresponds to credential dumping, command-and-control, or privilege escalation, enabling faster triage and response.

Optimized for Practical Investigation

Security professionals often need to cross-reference findings in a hex editor. mStrings accounts for this by capturing detailed string locations in hex, allowing for immediate context when reviewing suspicious files. This level of granularity is particularly valuable when analyzing packed or obfuscated malware, where offsets can provide crucial insights.

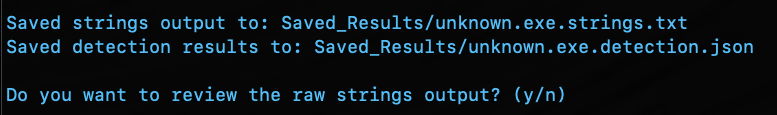

After the scan, reviewing the complete strings dump is just as easy with an option to open the results directly in VS Code.

Technology That Powers It

Built in Rust, mStrings leverages its robust ecosystem to enhance performance and reliability. Sigma-based detection rules allow for flexible and easily modifiable patterns, giving analysts control over what indicators to track. The tool’s structured approach ensures that results are not just extracted but meaningfully categorized for deeper analysis.

A Tool That Grows with You

mStrings is extensible, enabling you to customize detections. Not satisfied with the existing detection rules? You can easily write your own in Sigma. Future improvements will refine regex patterns, enhance Windows compatibility, and introduce new features to improve investigative workflows. Designed with usability in mind, mStrings serves as a practical companion for analysts who need clear, structured, and insightful data extraction.

MStrings is one of many malware analysis utilities included in MalChela. Download from Github and let me know what you think. If you’ve already installed Malchela, git pull will download the latest updates.

https://github.com/dwmetz/MalChela

Try this out for a workflow. Use Hash It (3) and give it the file path for a malware file. Use the hash from Hash It and check it against VirusTotal an Malware Bazaar with the Malware Hash Lookup (10). Then jump into mStrings (4), give it the same file path again, and start pulling out the interesting strings. Once you have what you think is a good number of indicators, run Strings to YARA (9) and generate a fully formatted YARA rule for use in any of your security tools.